A few thoughts on leading organisational transformation while balancing alignment and autonomy.

No Plan Survives Contact with the Enemy

The young emperor Napoleon was standing opposite Prussia on the 14th of October in 1806 when a mere 87.000 French soldiers clashed with no less than 143.000 men in the Prussian troops outside the city of Jena. Even though the Prussians were superior in number, they were restrained by a rigid system of command. This turned out to be fatal.

Already from the early hours, the battle was surprising – a French Marshal risked an unforeseen and hazardous solo attack on the Prussian flank. The Prussian supreme command was too slow to respond before the fifth French corps made it to the scene to help their fellow countrymen.

Now, Napoleon exploited this unpleasant surprise by letting the elite force of his army aggressively advance towards the middle of the Prussian army. Again, the Prussians did not react in time, and their lines broke down as their soldiers started running away.

Now the house of cards came tumbling down. On the same day, another French win took place after which the Prussian king ordered retreat. The French victory was massive, and the Prussians would be under French supremacy until 1813.

The defeat at Jena taught the Prussians about the means of control when two armies collide on a battlefield. No plan survives the first contact with the enemy.

Time for change - Identifying the gaps

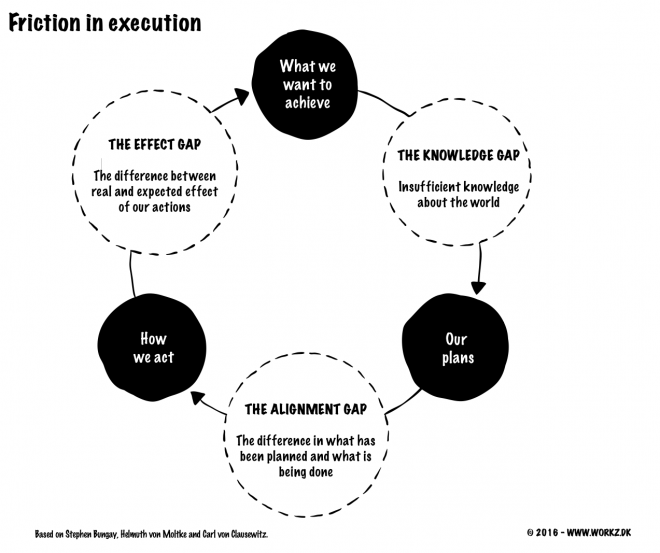

The defeat initiated a fundamental reformation of the Prussian military. The key figures in this reform work were, among others, Gerhard von Scharnhorst, Carl von Clausewitz, and later Helmuth von Moltke, who was born in Denmark. The Prussians identified three gaps of their leadership approach.

The first gap is the knowledge gap, understood as the difference between what we think we know about the world, and what the facts really are. Perhaps we believe that the enemy has 10.000 tired men and we plan accordingly, but in fact he has 20.000 rigorous soldiers. Our insight is limited, especially when it comes to predicting the future.

The second gap is the difference between the planned actions and what is actually being carried out in our troops or our organisation. Most people will recognise situations from their professional life where planned activities are heavily modified or simply not carried out. Now add the unplanned things that will surely happen, and we realise that the shift from planning to implementation is never straight forward.

The third and final gap concerns the effect. Often, we are surprised by the results of our actions. Perhaps we assumed that the enemy would surrender if we opened fire at them from a hilltop, but instead they might dig themselves in and wait for our ammunition to run out. During the planning phase, it is very difficult to predict which actions at the frontline will get you the desired results.

All things considered, it is extremely difficult to lead an organisation, be it an army or a business, when the battlefield is complex. How we understand and manage the three gaps depends on our leadership approach and the narrative running through an organisation. The Prussian narrative was one of control.

From Micromanaging to Radical Delegation

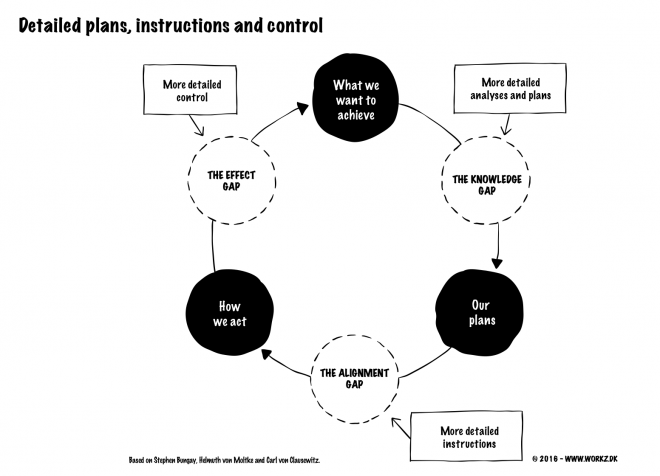

Before the battle of Jena, the Prussians regarded their military as a machine. Every soldier was a tiny, controllable component. In this mechanical approach to leadership, the solution was always in the details.

They attempted to close the knowledge gap by making detailed analyses to match the complexity of the battlefield. The more information, the better. The attempt to solve the alignment gap was also addressed through detailed instructions. The idea was that very specific orders would rule out any misunderstanding or improvisation. When facing the effect gap, the Prussians’ disappointing results were met with detailed control. Did the cannons have the correct powder load? Was the infantry in the correct shooting formation?

However, after the defeat, Clausewitz and his colleagues realised that it was useless to try and fix the machine by going into detail. Detailed instructions can make sense in isolation, but details did not help the organisation defeat the enemy on the battlefield. Instead of becoming better at handling high complexity, micromanagement only added even more complexity.

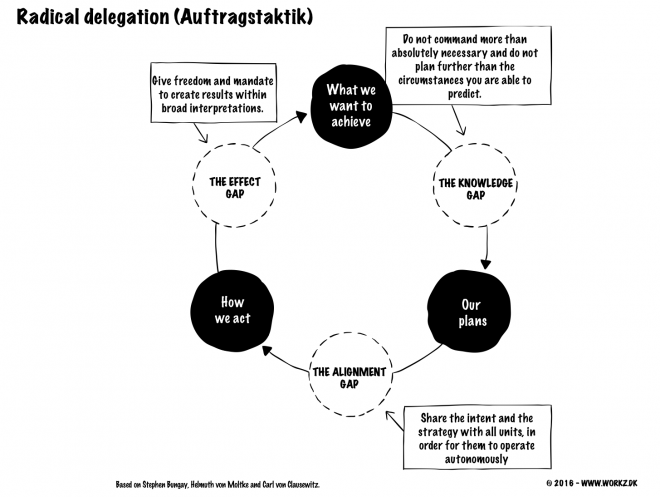

As a result, the Prussians replaced the organisational (his)story based on the mechanic approach and created an entirely new military academy, and instituted a new pragmatic military doctrine called “Auftragstaktik”.

This approach was radically different from the Prussians’ previous mindset.

Regarding the knowledge gap, the idea that analysis can solve complexity was left behind. Long-term plans were replaced by a much shorter planning horizon. Now, plans were simple working documents constantly being updated to reflect new knowledge.

In order to solve the alignment gap, the detailed instructions were replaced by simple orders giving individuals complete freedom to do what they found most appropriate to reach their goal. On the battlefield, if Prussians officers deemed something more appropriate in relation to the strategy, their duty was to ignore their orders and follow their own conviction. Without asking for permission.

In regard to the effect gap, the Prussian solution was to give a clear mandate to the officers at the frontline to try out different approaches. It is very difficult during the general staff planning to predict what precisely is going to work at the frontline. Therefore, the officers got extensive autonomy – they might have tried bayonets or hand grenades if it was not enough to just shoot at the enemy.

It took the Prussians 40 years to break free of the machine narrative. But the results were clear and from the mid-1800s, they had the most effective military in the world since Gengis Khan and Alexander the Great. Auftragstaktik was later adapted by all other armies, and in NATO it is known as Mission Command.

Autonomy and Alignment

The Prussian reforms rose out of the recognition that it is a complex, not a complicated, challenge to manage thousands of individuals, each with their own opinions, feelings and experiences. Leadership demands pragmatism and the will to let go of power at the operational level. Many leaders today still lack this understanding.

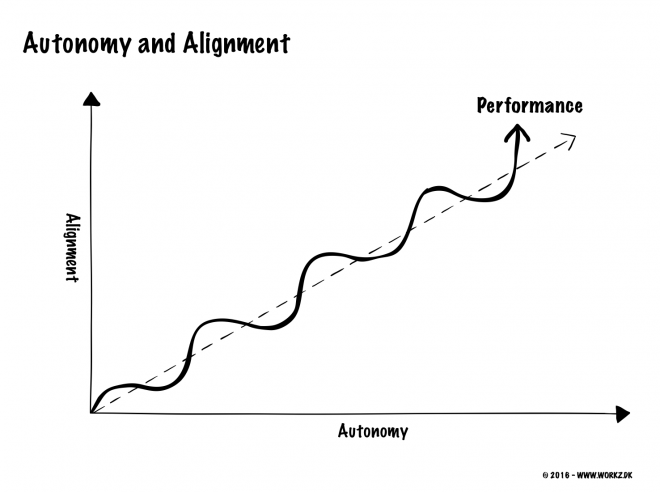

The focal point of the Prussians’ reflections was the relationship between autonomy and alignment. Normally, these two are considered complete opposites: command vs. freedom, control vs. trust, centralisation vs. decentralisation.

The Prussians concluded that an effective organisation requires a high level of autonomy as well as alignment. In other words, we have to act independently but in concordance.

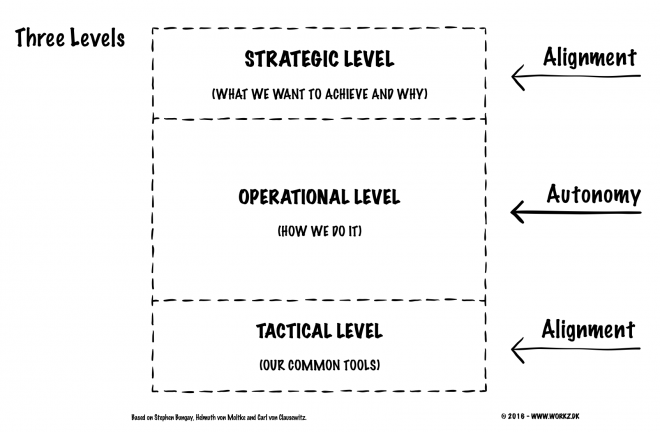

This is made possible by creating a clear division of labour between the strategic, the tactical, and the operational plan.

At the strategic level, it is all about Why and What. What are the strategic priorities and why are they necessary? This is also known as the Commander’s Intent. Here, there is a need for total clarity and alignment across the entire organisation.

On the other hand, there is complete autonomy on the operational level, letting each unit define its own ‘How’ individually. The objectives are fixed but it is up to the people in the field to decide how to contribute locally to achieve them.

The autonomy does have a limit, however, with regards to the common toolbox, also known as the tactical level. A Prussian officer was not supposed to start improving ways to erect a howitzer or advance in open terrain. The army’s basic toolset of small routines had to be adhered to – here, there was a demand for full alignment. The tactical toolbox was based on costly experiences and meticulous training in the military academies. It was a common language and common frame of reference that could not be questioned.

Thus, the autonomy of the individual was all about how he used the tactical toolbox to contribute to the common strategy in the best way possible.

Auftragstaktik Today

Needless to say, there are huge differences between leading a modern organisation and commanding a military force on the battlefield in the 1900s.

It is striking, however, how many of the Prussian experiences and ideas that are still relevant to challenges faced by both public and private organisations today. The mechanic understanding of organisations and leadership is still prevalent. Why have we not become wiser and moved on?

One of the reasons is that a counter doctrine arrived from the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. It was the American Taylorism that reintroduced the organisational machine metaphor, that the Prussians had left behind in 1806, under the tagline Scientific Management.

Frederick Winslow Taylor was an engineer and in his book, The Principles of Scientific Management, 1911, he presented a mechanical view on how to optimise the new industrial workplaces in the US. Taylor advocated specialisation, and quality control and he was not impressed by employees’ abilities to work independently. Taylor’s recommendations inspired, among others, the car manufacturer, Henry Ford, and they became very important in the US and later in Europe.

Measurement, optimisation and systematisation in organisational development certainly has its place in the right context, but as the Prussians experienced, Taylor’s principles are not sufficient when problems are complex rather than complicated.

Guidelines for business leaders today:

- Define and communicate Commander’s Intent. What is the situation, what do we want to achieve, and why is it important? Who is the enemy, what are we fighting for, and why is it so important? It must be brief enough to be written on a piece of paper that can be send to the frontline with a carrier pigeon. Ask the employees to repeat the task in their own words including a short presentation of how they plan to contribute to the execution (also known as back-briefing). That way you can make sure that misunderstandings are kept to a minimum.

- Put up a few priorities that everyone can contribute to. Nearly all organisations try to do too much, too fast with too few resources. Prioritise hard and choose a few initiatives which, on the other hand, get maximum support and momentum.

- Allow employees to decide how they can contribute. They will make mistakes and do things their way, but their commitment of being involved fully makes up for your frustration of experiencing loss of control and direct power.

- Throw away the complicated plans and proceed by the method of trial and error. Unless you build nuclear power plants or container ships that have to sail for 40 years, then back off the long-term detailed planning and concentrate on the next important steps instead.

- Learn from your experience and adjust the plan continuously. Many organisations follow up on whether the plans have been adhered to or not which is foolish, really. Follow up if you are getting closer to a victory and update the plan accordingly. Alongside that, you are learning from your mistakes.

- Utilise and respect the common tactical toolbox and make sure it is clear and well designed. If you delegate and give your colleagues freedom, they will drop all systems and tools that do not directly help them to achieve their goal. Good tools have to be helpful, not a burden.

- Show trust and increase transparency within the organisation. It is essential that we dare to share our mistakes and learnings. This requires people to feel safe and respected. A good way to facilitate this is to start talking openly about your own failures and insecurities and asking for help when in doubt.