Two days of undivided attention from 300 top leaders. An eye-watering budget. A year’s worth of internal work hours in planning and organising.

Arranging a conference requires a lot of resources, but it is also an effective means to engage a selected audience in dialogue and give them the necessary tools to contribute effectively towards a common goal.

What could possible go wrong?

Practical mistakes, like issues with catering, confusing signage, or timetables that don’t hold, can easily taint a conference experience.

Even worse is a situation where the content and proces of the conference falls short.

What if your message gets watered down or distorted, and dialogue with participants doesn’t run to plan? And what if the critical voices steal the stage?

An experience of wasted time, irrelevant topics, or confusion in processes, points directly to the relationships, reputation, and credibility of the organisers. It turn this may reflect badly on the very organisation, initiative, or project they wanted to present in the first case.

These risk make many organisers go for a conservative og restricted approach in designing the summit. Doing so they risk falling in to even worse pitfalls.

1. Lack of relevance

Nothing is more important to a conference than the feeling of relevance it creates. Attending a summit has to feel like it is worth the time. If you see a participant using her phone it means that whatever happens on the phone is more relevant at that moment than what happens on stage.

A smooth delivery in other aspects can not save a conference if the content is off. Lack of relevance creates a wall that prevents the participants from engaging with the process.

Irrelevance can arise due to a number of issues. A strategy conferences that is too focused on events of the past year, in stead of involving participants in a discussion on future direction. A generic keynote presentation from a celebrity speaker that is in discord with the topic of the conference.

To ensure relevance, the organisers need to know their audience and the expectations they have going into the event. Participants should be provided with information that is valuable to them.

Ask future attendees what they would like to get out of the summit, how you can best help them engage with the topics.

If possible have the attendees chose from different tracks to make sure they do not end up having to spend time on irellevant content.

When asking the participants to deliver input make sure to communicate the value of that input to the organisers. If it is not relevant to them, make sure they know it is relevant to you.

And always ask the participants if the content was relevant to them, when evaluating conference afterwards.

2. Unclear proces

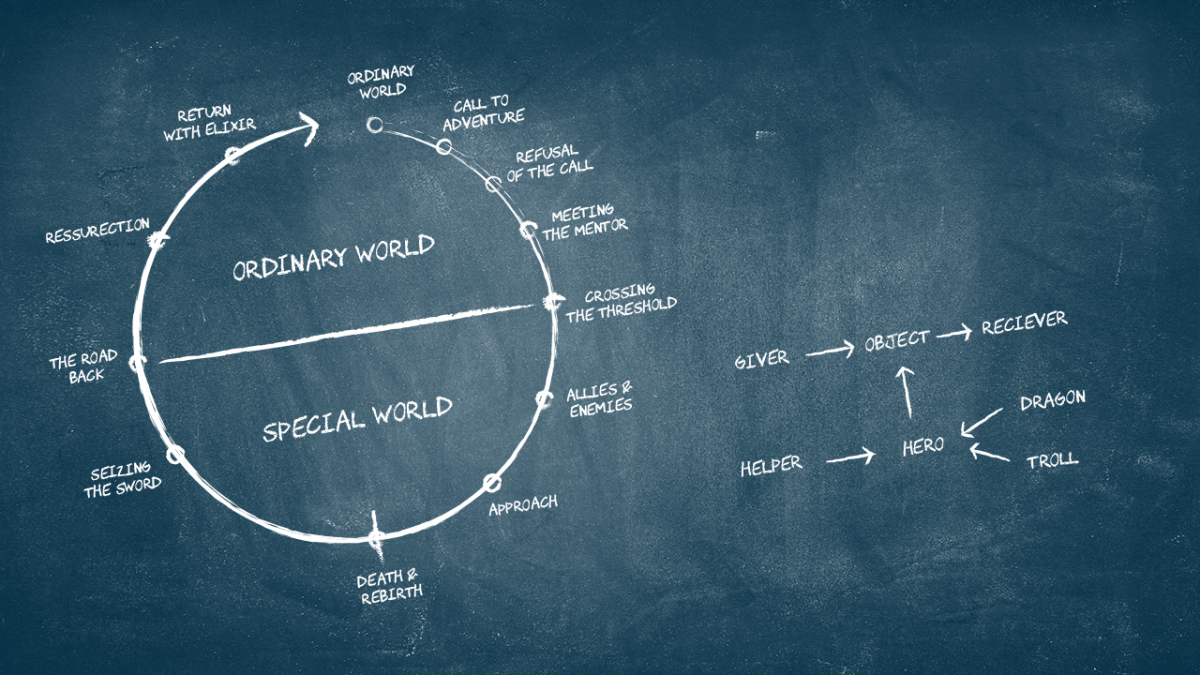

A conference is a journey. The attendees enter at one end, and come out, transformed, at the other. The path have to be logical, interesting, and meaningful.

The programme should reflect this and advance in a rational order: begin with the What, move on to the Why, and finish with the How. As one part closes, another opens, creating a logical sequence of events that ensures that your participants stay on track.

The process will seem rushed if the participants are not given the chance to digest and reflect. The participants should have the chance discuss all new themes of content with each other and to consider the significance of the input, as well as to think about what it potentially means for them.

Too many speakers competing for the participant’s attention, each presentation being a small journey in itself, will make the process seem unclear. This leads to a conference without clear priorities and focus.

A explicit outline of the proces in the programme will help create a sense of logic. It helps participants to know what is expected of them and when they will get answers to their questions. It is easier for participants to act according to expectations when presented with the right information.

Without a red thread each new part of the programme will make the participants feel like they are back to the beginning.

Although you’ll need to think of the big picture, don’t forget to keep a good eye on the details – a surprise that is announced on the agenda is hardly a surprise at all.

3. OUT OF BALANCE

The two worst ways that a conference can be described as are ‘boring’ and ‘too much of a show’.

Participants are no longer satisfied with two days of passively being on the receiving end of one-way communication. It does not matter of it is movies, lectures, or Powerpoint presentations. Too many, and too long, presentations without pauses or possibilities for involvement will make a conference boring to the participants.

Features that promise involvement or interactivity but end up as one-way communication will share the same fate.

On the other hand, the whole thing will turn into just a show, or a farce, if the programme and theme of the day do not match. Like a conference that address austerity, cuts, and financial difficulties, but has clearly splashed out on lavish food and staging. Or having top management involving in entertainment, when it does not come naturally to them.

It is also hard to be relevant to the attendees if you spend all your resources on entertainment.

The trick is to create the right balance between content and entertainment, with respect to the audience and subject matter. Some things are better suited to a dance performance than others. Too much involvement at the expense of communication also runs the risk of diluting the power of the message.

On the other hand, entertainment and interactivity are needed. A top manager who is open and shares their private self can prove to be extremely effective – when done right.

AT Workz we often addressed the need for balance through the use of simulations, games, and game-like processes. Doing this combines entertainment, involvement, and substance in a unique way.

4. PSEUDO INVOLVEMENT

The move from one-way communication carries the risk of pseudo involvement. Asking questions without really being interested in the answers. Asking for input without a clear idea of how to put the results into use afterwards.

Pseudo involvement comes in many forms. It could for example be a question hour with management where employees don’t feel like they can ask the questions they’d like to, or where the management responses are not authentic; or another classic, a panel debate with too many participants and too little time for answering the questions, or questions that are clearly pre-selected to fulfill a certain agenda.

A rushed attempt at co-creation, without focus and proper preparation, quickly turns into a loose brainstorm with endless post-its, plenty of frustration, and no follow-up.

Involvement on false premises damages the relationship between organiser and participant when they feel that you talk down to them and waste their time.

If you do not wish to involve your participants in the important decisions, make it clear from the start, and find something else to involve them in.

5. NO LINK TO EVERYDAY LIFE

The last pitfall on the list is perhaps the most important.

As special worlds of their own, events risk being experienced as isolated from the everyday lives of the participants. Lessons learned are quickly lost and left behind at the exit, if the participants do not receive support in connecting them to their daily practise.

Even the bast laid plans have a hard time surviving when the conference draws to a close and the participants leave. Reasons are forgotten, important obstacles overlooked and new critical voices emerge.

Spending too much time trying to convince the attendees and too little time helping them to bring the message back home or neglecting to address important obstacles is two of the causes of this.

Reality is hard to change. Even though the attendees comes back changed by the event, everybody else are just the same.

One way of avoiding this pitfall is to allocating time at the conference to deal with what happens afterwards. Have the participants make plans for their next step and make arrangements for follow-up procedures.

Use the participants as experts on their own context, and provide them with help and tools to build the bridge back home.

What then?

How do you avoid these pitfalls then? Read the next instalment in this miniseries and learn how to design effective summits.