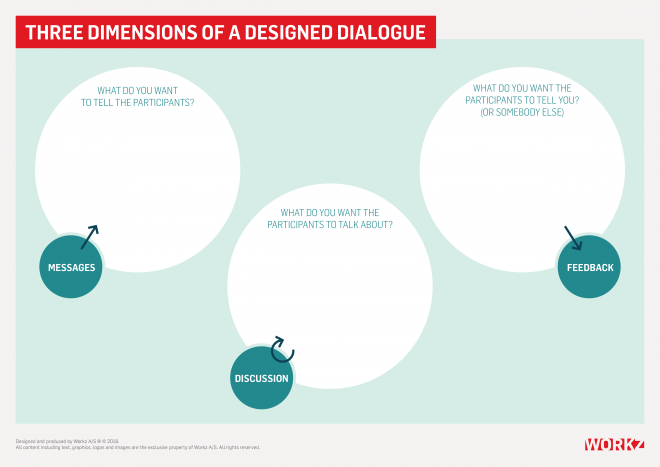

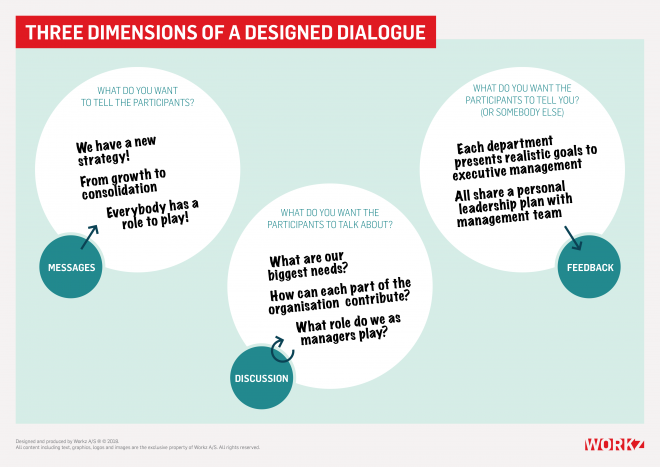

Three dimensions of a designed dialogue

Three questions you have to ask yourself when designing a dialogue.

Whether you are introducing a new strategy, teaching new skills with a serious game or changing mindsets through a workshop, a large part of the effect comes from the dialogues the participants have across the table.

Much of our work is done by having the right people have a productive and meaningful conversation together. But the moment you have more than a handful of employees, multiple layers of management or a complex challenge, having a good talk becomes challenging. Constructive conversations in this context need help and support.

When we design a learning game, develop a workshop or plan a full engagement campaign, we are in essence helping our clients have good conversations on what matters the most to them.

We call that designed dialogues.

Designed dialogues

At Workz, we design dialogues that are scalable, repeatable and predictable. Scalable in the sense that our solutions make it possible to have the same dialogue with a lot of people at the same time. Repeatable in the sanse that the dialogues can be had on multiple occasions and with different people with a similar outcome. Predictable, not in the sense of knowing what conclusions people will come to, but in the sense of being certain that the dialogues focus on the right things and are kept productive.

When designing dialogues, it is practical to look at three different exchanges of information within the larger conversartion. It does not matter if the discussion takes place around a single dialogue tool or is spread out across two days of a management meeting. We look at the information you want to feed into the conversation, what you want the participants to talk about between themselves, and finally, on the feedback you want to receive back from them.

Important objectives like networking, trust and buy-in require that you pay attention to all three parts of the dialogue.

These three questions is an effective framework to use during the preparation of events, no matter the size.

What do you want to tell people?

The first question is the easier to answer. You have some messages that you want to communicate to the participants. The traditional approach is to focus on reducing the amount of content and concentrating only on the core messages and key points you want to address.

This area is where most organisers feel most at home so they tend to give this part a lot of attention (and time on the schedule). They see the dialogue as a matter of communication and forget to listen. It is a far too common pitfall to spend so much time talking to the participants that you leave them no chance to talk back to you or room to reflect and talk to each other.

It is also important to note that not everything can be communicated by telling it explicitly. Some things are better practised than preached. If your core message is that you have faith in your organisations ability to adapt to market challenges, the best way of demonstrating this might be by asking for their visions of the future and ideas for handling upcoming issues.

What do you want people to tell you?

The next question deals with the kind of feedback you are looking for. Having brought a lot of important people together in the same room is a valuable opportunity to not just get your point across, but also to pick their brains.

You should only ask for input that is valuable to you and that you are willing to use. Asking for feedback is a great way to create ownership and buy-in, but only if the participants believe that you will use their input going forward. Always ask difficult questions that only the participants are able answer. Treat them like experts. If you do not see them as experts, it is a clear sign that you are asking the wrong questions.

Always tell people how you plan to use their input. And tell them again when you have used it and what the value was to you. This is also a perfect way to keep the dialogue going after the event.

Asking for feedback is also a good driver and a way to boost the energy level of the participants. It introduces a lean-forward dynamic to an otherwise passive experience. But be ware of asking for feedback without giving the participants time to reflect and talk to each other. A hasty poll on an over-simplified topic is the perfect way to ruin their faith in you taking their feedback seriously.

What do you want people to talk to each other about?

The two first dimensions are actually both one-way communication. By combining them, it looks like a dialogue; I tell you something and you reply. But without a discussion, it is just two monologues. It is in the discussion that the perspectives change, knowledge is shared and ideas are exchanged.

Some people shun away from free conversation because they cannot control the output. To them, discussion is a mine field. They may try to suppress it by only allowing one-way communication in the programme. The problem with this approach is that the conversations are not prevented – they are just forced underground or outside the structure of the meeting or workshop.

More often though, the time for discussion is slowly squeezed out of the design process because the effects are invisible. It is not that the organisers disagree that it is important, in principle. They just think it is less important than the other things they are trying to achieve. Open conversation rarely has a champion in the steering group.

Do not fall into the trap of letting time to talk compete with other objectives. Instead, see it as an enabler of everything you are trying to achieve. A mindset is one of the few things you can change by just talking about it. Have people talk about global issues the right way will introduce a global mindset. Discuss the path to success and you develop a winning attitude.

Just like treating the participants as experts when asking for feedback, the open dialogue has a guiding principle as well. Always have people talk about things that matter to them. Have them talk about themselves and try to keep the conversations on the specific and not the abstract.

Making people talk

Like a fire needs fuel, air and heat, a good conversation needs participants that a willing and able to share, a guiding structure and room for dialogue.

Everybody can have a dialogue, but some people are easier to get started than others. Recruit people to your event that are good at talking and able to have an open disposition. But make sure you do not exclude important perspectives by only recruiting yay-sayers. Make sure to help more introvert people express their thoughts as well.

Give people more ways than one to contribute and mix people in a way that keeps the conversation dynamic. Have people who share a role or background dive deep into a topic – or mix people from different background to open their minds to more perspectives.

The guiding structure can be an outside process framing the conversation and leading the participants along a certain path. You may ask for a specific piece of feedback because you know it will create the discussion you are looking for.

At Workz, we often use games and game-like dialogue tools to help drive conversations. Tools are a great way to kick-start a conversation. They allow you to inject bits of information along the way to fuel the conversation and introduce new perspectives or subjects. Finally, dialogue tools are a good way of keeping the conversation constructive and on the path towards a specific outcome.

The room for dialogue exists in space and time, as well as in a more abstract sense. Your venue and seating arrangements must be designed in order to facilitate the kind of dialogue you want. A theatre seating creates very different conversations from intimate four-man groups sitting in sofas. You also need time to talk. Set aside amble time for everybody to have chance to say their part – and even more if you want people to agree on something.

But most importantly, you need to make room in the information exchange for people to talk. If everything is said already, there is nothing to discuss. Only saying what is absolutely necessary, being curious and open about what you do not know and leading by example by having your hosts share their thoughts in an open way, are all good ways of creating a room for dialogue.

Be ware of creating a dishonest room for involvement where you promise to listen and use the input without intending (or being able to) actually follow up on the promise. In this case, you should ask a different question or start another, more realistic conversation.

Keep the dialogue going

When you have succeeded in getting a good dialogue going, it is a shame if it stops the moment the participants leave the room. As with most other interventions, a designed dialogue is more effective if it lives on and merges with the life outside the training session, workshop or summit.

This topic is for another post, but the tricks include all kinds of follow-up, social commitment, community building, the use of open endings, early prototyping and easy first steps.