Game-based learning is receiving more and more attention as a learning and development tool in the educational sector as well as in the corporate sector.

This article provides an overview of different kinds of learning games and provides a range of perspectives on how learning games can be utilised in actual organisational development.

In Denmark, learning games are already part of the range of organisational development tools in several companies. Large business enterprises such as Arla, Maersk, Vestas; Novo Nordisk and ISS use game-based tools in their ongoing processes and educational programmes and a number of organisations have bespoke games designed in order to train the participants in dealing with specific challenges such as focus on bottom line in the product portfolio, market understanding or value chain comprehension. Most large consultancies offer different games as part of their services and some – such as BTS (Sweden), Twynstra Gudde (Holland) and Workz A/S in Denmark and many more – have made it a strategic venture to offer bespoke as well as generic games.

People often connect games – and therefore also learning games – with computer-based games – but there are different types of game medias that each offers unique benefits that should not be overlooked. As this article will discuss, board-based learning games are a strong contender, just as the role-playing game genre is very widespread.

A BRIEF INTRODUCTION

Computer-based games can be utilised to model complex connections and to create engagement with picture, sound and IT-based solutions. An advantage to computer-based games is that the participants can use the game wherever they want and whenever they have the time.

Example: The Real Game

The computer game The Real Game focuses on business processes in a company’s supply chain. The game is developed by the Finnish scholar Timo Lainema from Turku Business School. The game is set in a fictive manufacturing company producing high-level hospital equipment and the participants work in groups a with a range of difficult decisions. The game has a very high number of parameters and gives the participants a clear view of how complex driving an efficient production process is. The participants are typically middle managers – e.g. production managers. During the game the participants have to make complex decisions that enables them to influence almost everything in the supply chain: wages, production quality, structure for sub-suppliers, financial management, investments in and optimisation of the production machinery, pricing and sales channels among many other factors. The strength of the game is that it, compared to many other IT simulations, clearly shows the cause and effect relationship while at the same time showing the complexity of running a profitable, operationally reliable and controllable business process.

The game is used to strengthen the business awareness in managers, to support decision processes in management teams and for educational purposes in business schools.

IT-based learning games, however, can come up short in the sense that they become a ”black box” to the participants in the way that the cause and effect relationships between the input of the participants and the output of the game is hidden in the algorithms of the software – the above mentioned Real Game example is one of the few, positive exceptions. Therefore, it becomes very hard for the participants to draw conclusions based on their choices during the gameplay. In group processes, IT-based games have another shortcoming since the participants all need to be able to see and navigate on the same screen which means that the person controlling the mouse often ends up making decisions on behalf of the group.

Board game-based solutions have now, in the middle of the digital era, begun to resurface. The physical representation that board games offer can be utilised to create a shared learning environment where the metaphors and objects of the game are visible to everyone. At the same time the game offers the participants a unique platform for creating a shared language and understanding of the subject matter theme. Board game-based solutions, however, also have their shortcomings: If rules and processes are inadequately designed they may obstruct the learning process. The participants then spend their energy learning the rules instead of learning the subject matter. A good learning board game creates learning of the subject matter while the participants learn the rules of the game.

Furthermore, a number of game-like exercises exist: Role-play-based training – for example training in the difficult conversation – has been utilised for a long time and in many different connections often combined with different process management approaches from business psychology such as the use of feedback techniques and reflective teams. Also, a range of process tools using game-like language or techniques from games exist: For example LEGO Serious Play which is a workshop-based process where the group of participants creates meaning in the organisation’s culture, strategy or other organisationally important subjects through building metaphors from LEGO.

GAME-BASED LEARNING

Let us take a step back and look into the origin of learning games. Games and simulation games (there is a difference but for now I will use the joint term ”games”) have been used for many years as an organisational training tool. The first traces of something that resembles a simulation game for military training go back to China 3000 BC. However, the first well-documented example is the original ”Kriegsspiel” that the Prussian army from around 1808 implemented in the entire organisation as a mandatory training tool for officers. The game spread out in a plethora of varieties to a range of armies and fleets all over the world.

Business simulations for training the strategic and operational competences of managers go back to the USA in 1956 where the ”Top Management Decision Game” was introduced.

Later on, the games have been dispersed over multiple disciplines and industries covering a range of leadership simulations: project management, change management, team management, sales team management, strategy implementation etc. Simulations that train a range of specialised disciplines such as portfolio management, supply chain management, crisis management, market knowledge, strategy development and innovation processes exist.

As a medium for learning games have a number of advantages – if they are being taken seriously as a medium and used by a skilled teacher. Games offer the participants an engaging form of learning that allows the players to interact dynamically with both theory and knowledge (Gee, 2003). At the same time, the players go through a game-based learning process where they test meaningful choices and solutions in a simulated praxis. (Magnussen, 2005) and thereby gain experiences based on the consequences of the game in a non-threatening learning environment.

Designing a game with the ”meaningful choice” as the point of departure is the primary objective of game design in general (Salen/Zimmerman, 2003) but when you develop a learning game it becomes a central element. Games are meaningful when the choices of the players deliver obvious feedback that is integrated into the broader context of the game.

In these processes the players can reflect upon their options in the game and mentally create future scenarios – e.g. best or worst case scenarios. This development of scenario competences in the learner holds a great potential for learning and is in itself an important competence in modern societies – including complex organisations (Hanghøj, 2008).

It is important to remember that modern learning games are not comparable to old well-known board-games such as Ludo or Monopoly that are built on a high range of randomness and very few meaningful choices. The inspiration for the latest learning board games can be found in what is called ”the new board game revolution”.

THE BOARD GAME REVOLUTION

Parallel to the boom in IT-based serious games and simulations another tendency can be seen, namely a rapid development of new design techniques within the area of board game-design and a reappearance of the board game as a recreational activity as seen with Settlers of Catan, Power Grid and many more.

These board games share a distinct design philosophy called ”Euro game” or ”German-style games” and are among other things characterised by innovative game mechanisms, a collaborative style and an absence of luck and random outcomes as driving factors. Many of these game design approaches and mechanisms have inspired a new wave of board-based learning games.

In a board game, on the other hand, unmistakeable links between the actions of the participants and the feedback of the game can be created since mechanics and process are visible to all participants through mutually accepted game rules and the physical objects of the game such as the game board, game pieces etc.

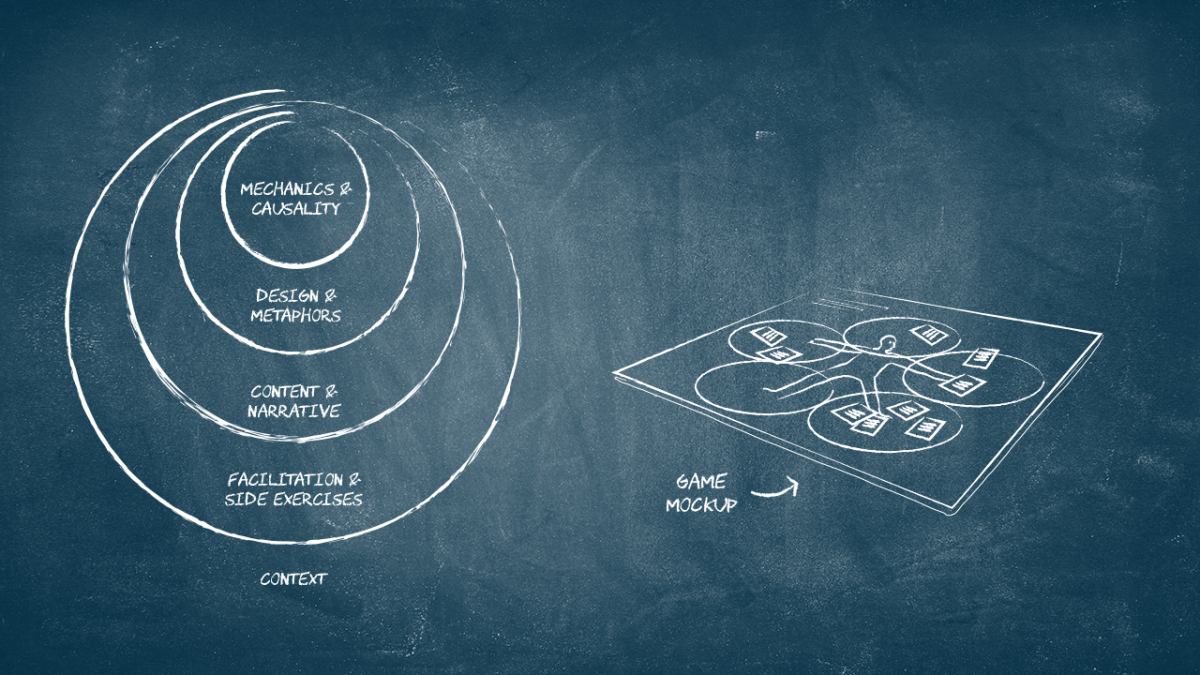

In a board game, however, you need to secure a deep and transparent embedment of the theme of the game in the mechanics of the game. In the case of ”serious games” it will often mean that the designer selects e.g. theory content or a process model that is then built into the rules and the process of the game.

When this is done successfully, the game creates a valuable, educational and direct interaction with the content as well as the mechanics of the game.

When we describe board games as effective learning games in this article we do not mean a simple rewriting of a question based quiz game such as Bezzerwizzer in order to make it about an organisation’s new sales processes. Educational board games need to be designed as a whole where the content and the process are inseparably interlinked.

THE MAGIC CIRCLE

The rules and context of a game are the most important structuring factors for the participants’ behaviour and what makes sense in the participant’s perspective:

“Within the magic circle, special meanings accrue and cluster around objects and behaviours. In effect, a new reality is created, defined by the rules of the game and inhabited by its players” - Salen / Zimmerman, 2004

”The magic circle” is a metaphor for the invisible border where a game begins and ends where you as a player consciously choose to accept the premise and fiction of the game. In the magic circle, the football ceases to be a ball made from pieces of leather and instead becomes an object you, as a player, can only touch with your feet. To play the game of football you have to mentally accept this premise. Otherwise the game does not work.

In our experience, game-based learning can produce unique results by deliberately crossing the border between the ordinary world – i.e. the daily practises and work-life of the participants – and the world of the game. This happens when the participants not only have to learn the game and its rules but are also ”forced” to discuss and reflect on the game by the facilitator. This is done either by drawing attention to contrasts between real-life experiences and occurrences in the game or by helping the participants apply conclusions from the game to ”the world outside” – i.e. making sense of the ordinary world by using the ”vocabulary” that the game process has created.

The game board and the table become a shared space – a conversational object that delivers content, frame and a procedure where the participants can explore, expand and challenge the perspectives that are brought to attention through their conversations across the board.

A BRIDGE BETWEEN ”KNOWING” AND ”DOING”

The learning board game can often be designed to function as a metaphor that can connect the experience and knowledge of the participants with a new awareness of possible actions.

This double purpose is seen in the design of the games Wallbreakers and Gamechangers – both designed by Workz A/S. The game board in both games functions as the physical components, that is necessary to play the game, and as metaphor-generating process tools that enable the participants to explore and identify new perspectives on known challenges.

In Wallbreakers that is a game about change management the ”Circle of change” (Maurer, 2010) is seen in the shape of the game board. Perspectives on resistance to the change process are represented by the positioning of the games pieces on the board: A bus represents the change process while the game pieces represent individual employees as being ”on the bus”, standing at the ”resistance pavement” or ”getting in gear”. The metaphor creates a concrete language about change for the managers who play the game; the goal is, of course, to get all employees on board.

The bus metaphor in the game Wallbreakers creates a language about change management. ”To be on the bus”, ”get off the bus” ”in front of the bus”, ”get into gear” become shared phrases when the managers discuss change management afterwards.

In Gamechangers, a game about strategy execution, the central metaphor is a five-masted sailing ship. The participants’ objective is, through the game processes, to put the right sails on the masts while avoiding obstacles. The sails represent factors that create momentum in the strategy while barnacles on the bottom of the ship represent external and internal hindrances to the strategy execution.

In games of this type the physical objects of the game can be viewed as metaphors that support the transition of practise-relevant learning that the participants have created through their interaction with the game.

BESPOKE PROCESSES

Software-based learning games such as simulations and games integrated into e-learning often create a closed learning process: the teacher or process facilitator cannot change the course or content of the process but has to follow the procedure that is embedded in the software. However, there is a range of practical benefits such as the fact that the “programme” is guaranteed to being delivered in a uniform manner each time. Moreover, concerning e-learning, the participants can access the learning material when they have time and they do not have to be physically present in the classroom.

Board games, however, leave room for the skilled board game process facilitator or instructor can adjust and customise the process, adjust the rules of the game or add extra exercises in order to expand or change the game experience, thereby providing other training goals than the ones initially suggested by the game. This can be done by, for instance, changing or adding actions in the game, including an extra theoretical perspective or by changing the objectives that the players aim for.

The attention of the participants can thereby be focused on selected themes or certain behaviour when needed. An option could be an extra process exercise that stages a difficult management dilemma relevant to the participants and which in a meaningful way can be added to the game-based training process.

LEARNING GAMES IN PRACTICE

Basically, learning games can be utilised in two types of situations:

- Education: as a part of an educational initiative for example as a single-day course or team event aimed at specialists or as part of an ongoing educational programme. Focus of the games is on the development of employees or teams on the individual level.

- As part of a strategic initiative for example an organisational change. Focus is on running the game at the organisational level i.e. emphasising and training goals, room for actions and success criteria in relation to a concrete change initiative. The purpose of the game is to support a change of perspective, culture, competences and focus in for example a group of managers.

Good advice

Companies that consider integrating learning games into their organisational development initiative, either as part of an educational programme or as part of a strategic initiative, should consider some simple points:

Is there a generic game that covers my need or should we go for a bespoke solution?

- Generic games are cheaper since they are already developed and many games can be adapted to a range of learning goals. They are field-proven and a broad selection that covers the most common areas already exists.

- Bespoke solutions specifically adapted to the concrete challenge that the company is facing can sometimes be an effective way of communicating a message or train a specific competence. If management needs to train the comprehension of the specific market situation or railway personnel needs to train specific professional roles it is quite possibly necessary to customise if games are to be used as a training tool

Should we run the game or do we need consultants?

- If the company is making a long-term investment in utilising learning games, training the company’s own employees in running and facilitating the games is probably the most cost-effective. Often generic games are linked with a certification in their use, as seen with for example personality profiling tools such as DiSC or MBTI, and after being certified internal consultants can run and facilitate the game.

- If it is just a single-use situation such as a team day event it will often be much cheaper to have external consultants run and facilitate the game – this way you are also guaranteed an experienced facilitator.

Board, IT or role-playing game?

– That depends on the use situation and subject matter:

- If the subject in question is difficult to simulate such as production management or market development, the best solution will often be it-based solutions since the computer is apt at handling the number of calculations needed in the simulation. If the flexibility that e-learning offers is needed, IT is also the logical choice – although the effect is not the same as in educational situations where the participants are physically present in the same room and the learning is group-based.

- If the purpose is to create processes where the participants as a group are to cooperate around a subject matter, learn from each other and make good decisions, board-based solutions will often be optimal. The board creates a natural collaborative situation that is well-known from family board games.

- If the purpose is competence development with the individual as the focal point role-playing games with built-in feedback processes could be the solution. This could be training of various types of professional interviews and dialogues concerning for example sales, dismissal, conflict management etc. When role-playing games are used you need to be very conscious about the staging and the feedback processes you design for the game and you should use an experienced process consultant as facilitator in order to avoid that the participants end up in awkward situations that get a little too close for comfort or that the feedback is not constructive.